Louise Bourgeois In Florence

to 20 October 24

All they want from you is to be yourself without shame and without false shame. Coward, madame, allow them to trust you. That’s all, don’t abandon them when you abdicate yourself.

Louise Bourgeois, Ode à Ma Mère, 1995

you need a mother. I understand but I refuse to be your mother because I need a mother myself

Louise Bourgeois, diary entry, 16 March 1975

There is great anticipation in Florence for the project organized and coordinated by Museo Novecento Louise Bourgeois in Florence, which will open to the public from 22 June to 20 October 2024. Two exceptional exhibitions – Do Not Abandon Me and Cell XVIII (Portrait) – will engage Museo Novecento and Museo degli Innocenti, consolidating the collaboration initiated in recent years between the two institutions. The project brings the works of Louise Bourgeois (Paris, 1911 – New York, 2010) to Florence for the first time, building a significant relationship of osmosis between her creations and the exhibition context. This is a recurring theme in the exhibitions of Museo Novecento, which has played an important role in diffusing contemporary and modern artistic languages in close collaboration with other major Florentine museum institutions.

Coinciding with the 10th anniversary of its opening, Museo Novecento thus celebrates Louise Bourgeois as one of the absolute protagonists of 20th and 21st century art with the exhibition Do Not Abandon Me, curated by Philip Larratt-Smith and Sergio Risaliti in collaboration with The Easton Foundation. Conceived in close dialogue with the architecture of the former Leopoldine building, a complex with a strong social vocation run for centuries by all-female communities, the exhibition will give the opportunity to experience almost one hundred works by the artist. These will include many works on paper created in the 2000s and sculptures of various sizes in fabric, bronze, marble and other materials. There is also great anticipation for Spider Couple (2003), one of Bourgeois’s most famous and emblematic creations, which will be installed in the museum courtyard.

For this special occasion, the collaboration with Istituto degli Innocenti will be revived. Founded in 1419 as a hospital with the specific purpose of welcoming children deprived of family care in an environment marked by high artistic and architectural value, the Institute has never interrupted its original mission, and is known for pioneering innovations for the care of the youngest children. In the complex designed by Filippo Brunelleschi, the Museum will host Cell XVIII (Portrait), a work of strong visual impact which powerfully resonates with the history and collection of the Innocenti, chosen by Philip Larratt-Smith in dialogue with Arabella Natalini, director of the Museo degli Innocenti, and Stefania Rispoli, curator of the Museo Novecento.

The exhibition Do Not Abandon Me, strongly desired by the director of Museo Novecento and whose gestation dates back six years, will occupy almost the entirety of the former Leopoldine building, between the galleries on the ground and first floors.

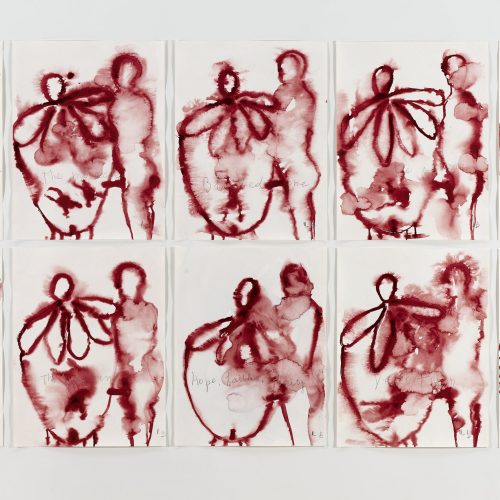

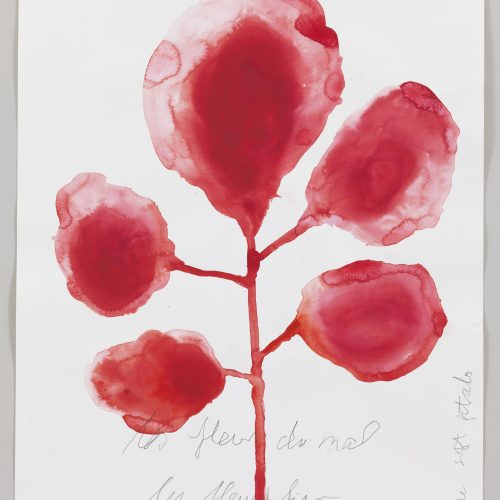

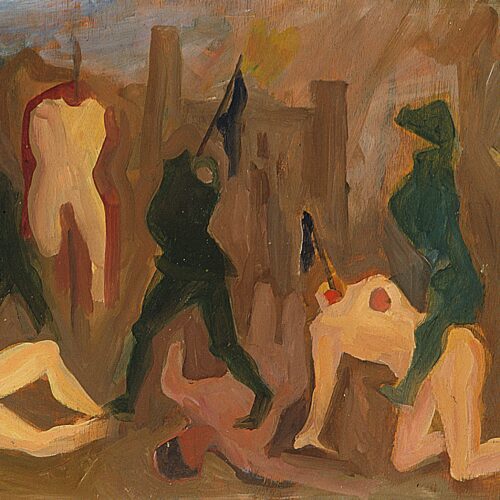

The exhibition will present a survey of Bourgeois’s late red gouaches with a thematic focus on the motif of the mother and child. The exhibition’s title refers to Bourgeois’s powerful and lifelong fear of abandonment, which here relates to the mother-child dyad that sets the pattern for all future relationships. Motherhood and all its discontents was central to Bourgeois’s conception of herself. At the same time, as old age made her frailer and more dependent upon others, there was an unconscious shift towards the mother in her late work.

Made during the last five years of Bourgeois’s life, the gouaches explore the cycles of life through an iconography of sexuality, procreation, birth, motherhood, feeding, dependency, the couple, the family unit, and flowers. In making them, Bourgeois worked “wet on wet”, which meant relinquishing some control over the final result and embracing the role of chance and fate. Red was Bourgeois’s favourite colour, and the intensity of the gouache is evocative of bodily fluids, such as blood and amniotic fluid.

Of particular interest is Bourgeois‘s collaboration with British artist Tracey Emin (Margate, 1963). On display will be a series of sixteen digital prints on fabric entitled Do Not Abandon Me (2009–10), created as a result of the two artists’ meeting. This was a project of great generosity and empathy between Bourgeois and Emin, and succeeds in communicating their own unique artistic languages while also creating strong visual compositions of understanding and tension, raising them to a universal level.

Exceptionally, the Museum’s cloister will host Spider Couple (2003), one of Bourgeois‘s iconic large-scale spiders, made in bronze. The exhibition will be complemented by the special display of two important installations: Peaux de Lapins, Chiffons Ferrailles à Vendre (2006), one of the artist’s Cells, presented in a room on the ground floor of Museo Novecento, and Cross (2002), presented in the former church of the Renaissance building, which women were once forbidden to enter during the celebration of religious rites, as evidenced by the women’s gallery separated by iron grilles.

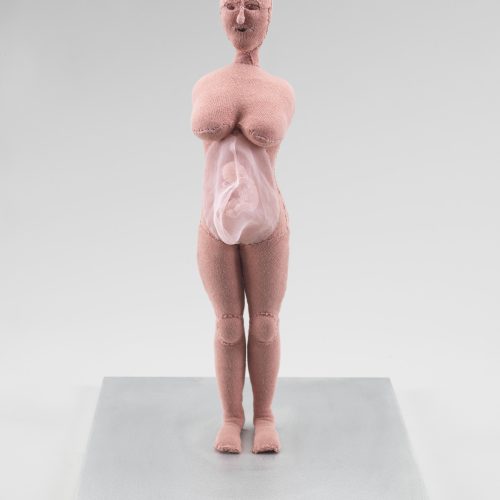

As part of the Florentine project, the Museo degli Innocenti will place Bourgeois’s Cell XVIII (Portrait) (2000) in evocative dialogue with some of the collection’s most iconic works. The rare cultural, historical, and artistic heritage of the Museum exemplifies the centuries-old history of the public institution, long characterized by the presence of a conspicuous female community.

Louise Bourgeois grew up just outside Paris, where her parents ran a tapestry restoration workshop and gallery. Her childhood was marked by complex family relationships, which led to traumatic experiences that were a major source of inspiration for her art. From intimate drawings to large-scale installations made in a variety of media, including wood, marble, bronze, and fabric, Bourgeois expressed psychological states through a visual vocabulary of formal and symbolic equivalents. The scale and materials of her works vary as much as the forms, which oscillate between abstraction and figuration. Emotions such as loneliness, jealousy, anger, and fear are common threads in her oeuvre. Her almost obsessive writing, as well as drawing, remained central forms of expression throughout her life.

Through her art, Bourgeois investigated the intricate dynamics of the human psyche and often stated that the creative process was a form of exorcism: a way of reconstructing memories and emotions in order to free herself from their grasp. Although initially she devoted herself to painting and drawing, it was ultimately sculpture that constituted a fundamental part of her work, centered on autobiographical elements often reworked in a metaphorical key. Bourgeois transposed family tensions and traumas, above all the complex relationship with her parents and its broken, damaged, but never severed ties, into numerous works that narrate the shattering experience of abandonment and the longing to connect. Her world of emotional intensity and obsession draws inspiration from the unconscious, seeking to express the unspeakable. Bourgeois thus opens up to a poetics of the uncanny, capable of exorcising trauma and inhibitions. The variety of mediums and techniques Bourgeois employed is extraordinary, and her fertile creativity, curiosity, and experimentation places her alongside the very great artists of the last century. Until the final days of her very long career, she was never idle, nor did she exhaust her intellectual curiosity and creative energy in definitive and repetitive paths and goals.

From her earliest works, Bourgeois established the relationship with the mother as an essential theme, and associated this from the 1990s onwards with the image of the spider. A major spider sculpture – in this case, a mother-and-child pair – will be displayed in the cloister of Museo Novecento as the thematic centerpiece of the entire exhibition. As has often been pointed out, the spider represents for Bourgeois a symbol of her mother, and as such it is the bearer of dual and conflicting meanings. It can be interpreted as the embodiment of extreme intelligence, a protective figure that provides for its young by building a home and securing food. Indeed, Bourgeois herself identified with the spider because she felt that her sculpture came directly out of her body, much as the spider spins its web. But it is also the manifestation of a threatening and disturbing presence, an expression of underlying hostility and aggression that collects and encapsulates traumatic experiences from deep within the unconscious. Thus, the installation of Spider Couple in the Renaissance cloister, designed by Michelozzo and traditionally intended for meditation and contemplation, becomes emblematic. Museo Novecento is also proud to premiere Spider, a floor sculpture consisting of a bronze spider and a mable egg which has never been publicly exhibited before.

Similarly, the choice to exhibit Peaux de lapins, chiffons ferrailles à vendre seems revealing. Among one the last works belonging to Bourgeois’s Cells series, which were first presented to the public in 1991 at the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh, its title refers to a childhood memory, that of the cries of rag pickers engaged in selling goods on the street. Within the Cell, Bourgeois inserts a number of sculptural elements that recall her personal and family history, such as cloth sacks and rabbit skins: components referring, respectively, to the empty womb and by extension the female body, and more literally to the animals hunted and raised by her family members. The name of the series plays on the multiple meanings of the word ‘cell,’ which can be translated into Italian into “cellula” or “cella.” It thus refers as much to the elementary unit of all living organisms as to the condition of isolation, separation, and confinement that characterizes a prison or monastery. These are meanings that take on special resonance within a building that over time has been a hospital, a place of shelter, a space for the education and reintegration for women, a school, and even a prison.

When first introducing her Cells, Bourgeois stated, “The Cells represent different types of pain: the physical, the emotional and psychological, and the mental and intellectual. When does the emotional become physical? When does the physical become emotional? It’s a circle going round and round. Pain can begin at any point and turn in either direction. Each Cell deals with fear. Fear is pain. Often it is not perceived as pain, because it is always disguising itself. Each Cell deals with the pleasure of the voyeur, the thrill of looking and being looked at. The Cells either attract or repulse each other. There is this urge to integrate, merge or disintegrate.”

Thanks to the installation inside a room on the ground floor of Museo Novecento, Peaux de lapins will reveal unprecedented associations with the life of the monastic community that animated the history of the former Leopoldine, a complex that was founded in the 13th century as a pilgrims’ shelter, and which then became a place of convalescence. Since the 16th century, in fact, its management was entrusted to the Franciscan Tertiary Sisters. Later, at the behest of Pietro Leopoldo of Lorraine, the management was entrusted to the nuns of the Conservatorio delle Terziarie (also known as the Giovacchine) and the Conservatorio di Gesù Buon Pastore (also known as the Stabilite), the latter in charge of, among other things, initiating poor girls into women’s work (hence the name “Scuole Leopoldine”).

Partial evidence of this long affair survives to this day in a series of frescoes, visible in the ground floor rooms of the museum where Peaux de lapins will be presented. Of particular note is a painting depicting a sister inviting silence: iconography, often used in the entrances of refectories and dormitories, that seems to act as a warning to anyone passing through these spaces by hinting at the need for recollection and contemplation even in environments intended for community life. And it is contemplation and silence that the visitor will be invited to consider along the path of the visit, inspiring an in-depth reading of the work and its themes, and even a personal de-construction and elaboration of one’s own social models and references, one’s own traumas, ghosts, and desires.

The Cell presented at Museo degli Innocenti also invites recollection and contemplation of spaces once daily lived, fitting within the Art route that unites the gallery above the Brunelleschian loggia of the façade and the rooms of the Coretto that overhang the ancient Church of Santa Maria degli Innocenti.

Although belonging to the same series as Peaux de Lapins, the subject of Cell XVIII (Portrait) seems to peculiarly reinterpret the iconography of Madonna della Misericordia, which recurs in some of the most emblematic works in the collection and strongly represents the Institution’s vocation of hospitality. In celebrating the role fulfilled by the Institution over the centuries, this image calls to mind the large female community composed of both the girls received and raised here and the figures who, by performing various tasks, have contributed to ensuring that the condition of women, and of mothers in particular, has become part of the institutional mission alongside the promotional activity on the rights of children and adolescents that is today identifiable with Istituto degli Innocenti.

Cell XVIII (Portrait) will therefore be in dialogue with that mission, in the spaces where different stories echo, steeped in the desires and fears also expressed by Bourgeois, which do not, however, exclude here the possible fulfillment of an expectation.

Simultaneous with the Florentine exhibitions of Louise Bourgeois in Florence project, at Museo Novecento and the Museo degli Innocenti, as many as three exhibitions will take place in other cities also devoted to the great artist. From June 21 to September 15 at the Galleria Borghese in Rome, Unconscious Memories will open to the public and at Villa Medici the exhibition No Exit. Naples will also pay tribute to Louise Bourgeois, with the exhibition Rare Language at Galleria Trisorio, which will be on view from June 25 to Sept. 28.

A new episode of the Labirinto900 podcast by singer-songwriter and historian Letizia Fuochi on the figure of Louise Bourgeois will be featured on the occasion of the exhibition. The museum’s public program, with events and screenings focused on the exhibition Do Not Abandon Me, will also be announced soon.

Sincere thanks for their kind contribution to the realization of the exhibition go to Castello di Ama S.r.l. – Società Agricola, Gianfranco d’Amato, Faggi Enrico S.p.A., Leofrance S.p.A., Maria Manetti Shrem, Giancarlo and Danna Olgiati, and Margherita Stabiumi.