Leonardo da Vinci and Florence

to 24 June 19

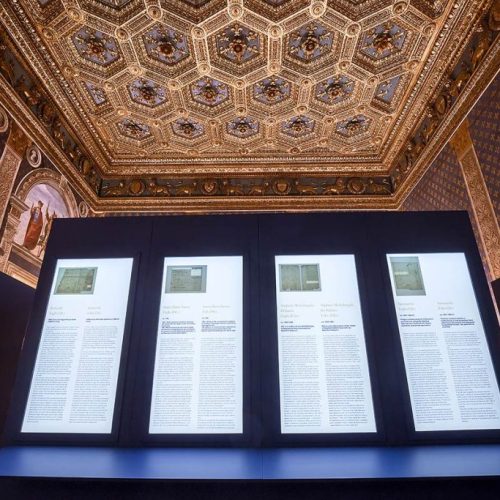

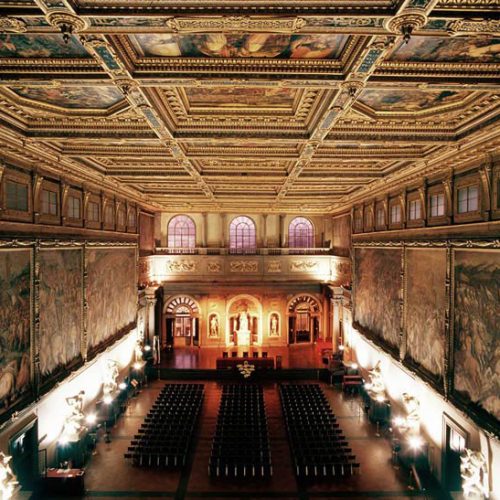

Palazzo Vecchio, Sala dei Gigli

Leonardo da Vinci died 500 hundred years ago in the castle of Clos-Lucé in France. Although he had been away from Florence for ten years, he felt a close attachment to his city until the end. All his life he called himself a ‘Florentine painter’: in his will he indicated that he wished to be buried at the ‘church of Saint-Florentin of Amboise’; the year before his death, he dedicated one of his last writings to the menagerie of lions behind the Palazzo Vecchio. The page on the symbolic animal of Florence testifies to a still vivid memory and bears the significant date of 24 June 1518, the day of the city’s patron saint. It is in the name of this connection that the city now renders him homage with the exhibition Leonardo da Vinci and Florence: Selected Pages from the Codex Atlanticus. On display at the Palazzo Vecchio – still today the most representative site of the city, as it was in the artist’s time – are twelve handwritten folios by Leonardo, from the esteemed Biblioteca Ambrosiana. The exhibition is curated by Cristina Acidini and runs from 29 March to 24 June 2019. Sponsored by the City of Florence, it is organized by Mus.e with the valuable contribution of ENGIE, a world player in energy and services, with activities aimed at making them a leader in the energy transition to zero CO2 emissions.

Preserved in the historic library of Milan, the Codex Atlanticus contains 1119 folios, mostly of writings and drawings by Leonardo da Vinci. This extraordinary graphic treasure is by no means unknown: in addition to the complete editions which followed the first one by the Accademia dei Lincei in 1884, scholars throughout the world have studied and published a number of its pages. In addition, since the meticulous restoration work on the Codex in 2008, the Biblioteca Ambrosiana has organized 24 exhibitions based on various themes regarding Leonardo’s multifarious interests. These displays highlighted the extent and nature of his genius, which Cristina Acidini characterises as ‘sublime, versatile and diffuse’ in her delightful introduction to the catalogue.

The twelve selected pages, which are not the only ones that allude to Florence, function as so many Ariadne’s threads in reverse: they guide visitors into the depths of the labyrinth rather than indicating the way out. Indeed the labyrinth is perhaps the best metaphor for Leonardo’s many-sided and often contradictory relationship with the city, in whose territory he was born and where he spent his formative years.

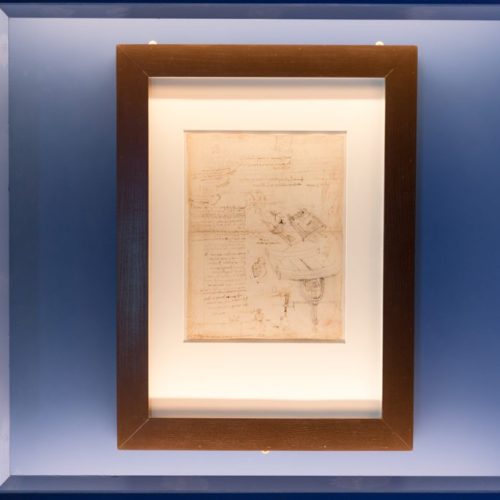

The exhibited folios range in date from the 1470s to Leonardo’s death in 1519; they each possess an extraordinary evocative capacity. Thanks to the contributions of experts in the various fields in question, the display explains why each page was selected. The first, for example, contains the noteworthy phrase, ‘Sandro, you don’t say why such second-level things appear shorter than [those in] the third [level]’. This has been interpreted as a criticism of Botticelli’s perspective, recalling the time when the two painters frequented Andrea del Verrocchio’s workshop, as they lay the basis for a relationship that was never devoid of rivalry.

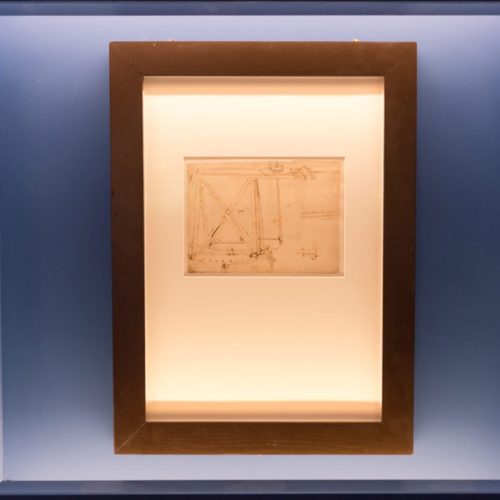

Leonardo entered Verrocchio’s workshop at a young age. At this rendezvous of artistic figures he learned not only the basics of painting but also the more difficult techniques of sculpture and metalwork. From another of his drawings displayed here, we understand that he had seen up close the gold-plated copper ball that his master had placed on the lantern of Brunelleschi’s dome in 1471. On this and on other occasions, he did not fail to study the machines at the Cathedral building site – still preserved at the Opera del Duomo – which he certainly recalled during his work as consultant for the construction of the dome cladding for the Milan Cathedral in 1487-88.

In Milan, Leonardo was in contact with Florentine merchants, bankers and travellers as he acted as liaison between the court of Ludovico Sforza and his home city, fulfilling a variety of tasks: indeed another of the displayed folios tells us that he was asked to procure a text on the government of the city of Florence probably written by Girolamo Savonarola, the Dominican preacher who established an ephemeral theocracy following the expulsion of the Medici, before being excommunicated and burnt at the stake in 1498. Leonardo certainly met him when the artist was consulted on the construction of the Sala del Maggior Consiglio, today’s Salone dei Cinquecento, in the Palazzo Vecchio.

After an absence of nearly 20 years, Leonardo returned to Florence in 1500, residing there on a regular basis from 1503. One of his points of reference during this second stay in the city was the great Hospital of Santa Maria Nuova, where he deposited his savings on the day of his father’s death in 1504, as testified by another of the pages on display. Here he also frequented the Compagnia di San Luca, located in the Hospital, and most importantly found the opportunity to study human anatomy through the dissection of corpses.

This was also the period of his great projects and ambitious studies. The folio which records the childhood memory of the ‘kite dream’ – which, as the catalogue reminds us, has taken its place in the history of psychoanalysis for having inspired Freud’s 1910 essay – reveals Leonardo’s passion for the study of flight: his observations of the movements of birds indeed became the basis for the vision of the mechanical wing that would give humans the ability to fly. This was in fact the period of the experiment of Monte Ceceri, if indeed such an attempt actually took place. At the same time, Leonardo studied Florence’s hydrography and the entire Arno Valley, proposing a change of the river’s course by means of a canal that would simplify its winding path. The displayed page alludes to an undertaking worthy of a pharaoh, so magnificent that it was beyond the means of Florence’s merchants.

This period, finally, was also that of the great artistic opportunity given to him by Pier Soderini, gonfaloniere of Florence: the realisation of The Battle of Anghiari, to be painted in the Palazzo Vecchio to rival Michelangelo’s Battle of Cascina. (The ‘instructions’ for Leonardo’s work are indeed given in one of the exhibited folios of the Codex.) This work was planned with drawings, cartoons and preparations of the wall, yet once executed it quickly deteriorated, an occurrence which certainly pained Leonardo and which he perhaps considered a partial failure.

Shortly thereafter he was back in Milan, in the service of the French; from there he travelled back to Florence and then to Rome, where he consolidated his relationship with the Medici family – and in particular with Giuliano, son of Lorenzo the Magnificent – at the court of Pope Leo X. Two pages on display demonstrate his ties to the Florentine dynasty, which began in the final decades of the Quattrocento under Lorenzo’s protection and continued with his descendants. Yet this relationship was not without tension and took a grievous turn upon the death of Giuliano in 1517. Leonardo then left Rome for France, in the service of Francis I.

Leonardo’s career was a complex one: he received many prestigious commissions which did not always produce positive outcomes; yet his curiosity was always insatiable. Throughout his life, Florence was his primary point of reference, whether he found himself in the city or far from it. The pages on display in this exhibition show visitors the important role played by Florence in the artist’s life.

The exhibition closes with a single painting, which acts as a counterweight to the drawings: this is the Busto del Redentore (portrait of Christ), by Gian Giacomo Caprotti – known as Salaino – and on loan from the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, to which the work was donated in 2013. The painting introduces a new topic into the display, as it is neither a work by Leonardo nor a reference to the master’s relationship with Florence. Nonetheless, the painting has a mysterious but undeniable connection with Salaino, whose signature it indeed bears. Also called SALAI, this painter was one of Leonardo’s favourite assistants, having certainly been trained by him in Florence during the opening years of the 16th century. Characterized by an iconic steady gaze and remote tenderness, this portrait clearly reveals Leonardo’s influence. It will no doubt continue to provoke thought and even controversy, which is, after all, the most we can ask of an artistic exhibition.

Curated by

Cristina Acidini

Sponsored by the

City of Florence

Organisation and coordination by

MUS.E