Jeff Koons in Florence

al 15 January 16

Florence, 25th of September, 2015: for the first time, in nearly five centuries after the Hercules and Cacchus by Baccio Bandinelli (1493-1560) was put into place, an original sculpture of remarkable dimensions will be placed in front of Palazzo Vecchio. It is Pluto and Proserpina by Jeff Koons (1955), a monumental work measuring over 3 meters. An extraordinary event inaugurating the project In Florence, an ambitious and innovative plan providing for a meeting between the artistic protagonists of our time and Florentine Renaissance spaces and works.

Jeff Koons In Florence, an eagerly anticipated exhibition of the year explores the relationship between the provoking beauty of the works by the brilliant American artist and the timeless masterpieces by Donatello (1386-1466) and Michelangelo (1475-1564). The locations chosen for such a juxtaposition are theRoom of the Lilies in Palazzo Vecchio and Piazza della Signoria. This exhibitions is made possible thanks to contributions by Fabrizio Moretti, new Maecenas of Florence and contemporary art, internationally well known as an old master paintings dealer.

Palazzo Vecchio will host Gazing Ball (Barberini Faun), a work created in 2013 belonging to Koons’s series called Gazing Ball, which features plaster casts of famous sculptures of the Greco-Roman period, as well as everyday objects encountered in the suburban landscape, each affixed with a bright blue reflective glass sphere. A sophisticated and seductive conceptual act of art takes place with the artwork in this series, for they, overturn and divert the gaze of the observer from the admiration of the classical piece or traditional object, and create a memorable image of pure perfection. The environment as a whole, including the observers themselves and the various elements of their surroundings, become a part of the artwork itself. Koons’s Gazing Ball works plays with the seductive nature of the plaster cast, so pure and rarefied, and the mysterious magic of the blue gazing ball with its mirrored surface.

The ancient Barberini Faun, (“Uno fauno a sedere più grande del naturale quale sta dormendo e tiene un braccio in testa” Archivio Barberini, Roma, 1632), is a sculpture of the imperial age probably inspired by a bronze of the Greek Hellenistic period discovered in Rome in the moat surrounding Castel Sant’Angelo around 1624. Four years later it entered the Cardinal Francesco Barberini’s collection and then reached Germany at the beginning of the nineteenth century (now to be found in the Glyptotheque in Munich). Some restoration on the work was carried out either by Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598-1680) or possibly by his workshop.

This is how Koons explains his work: “I’ve thought about the gazing ball for decades. I’ve wanted to show the affirmation, generosity, sense of place, and joy of the senses that the gazing ball symbolizes. The Gazing Ball series is based in transcendence. The realization of one’s mortality is an abstract thought and from there, one is able to have a concept of the external world, one’s family, community, and a vaster dialogue with humankind beyond the present.”

The gazing ball can also be seen as a symbol or an archetype of the perfection of the universe, of the One, of the Infinite and the Eternal – as in the Timaeusby Plato – and then delicately placed on the sleeping Faun’s knee, constantly reflecting the ever-changing external world.

The Gazing Ball series takes its name from the round lawn ornaments Koons frequently encountered around his childhood home in Pennsylvania. Gazing Balls were likely first produced in Venice, Italy in the thirteenth century, and then were popularized in the nineteenth century by King Ludwig II of Bavaria by his displaying them throughout the gardens of his palace, and likely made their way to Pennsylvania through the Europeans who settled there. The power these objects offer is to enable the observers to see the vastness around them, absorbing in the reflection of one’s own image and all the elements that surrounds one’s body. Fascinating, magical shapes that are to be enjoyed not only for their lightness (they are made of blown glass), but also for their association with generosity, and for their allusion to the fleeting duration of life – as with soap bubbles.

As Koons states: “The Gazing Ball series is based on the philosopher’s gaze, starting with transcendence through the senses, but directing one’s vision (the philosopher’s gaze) towards the eternal through pure form and ideas.”

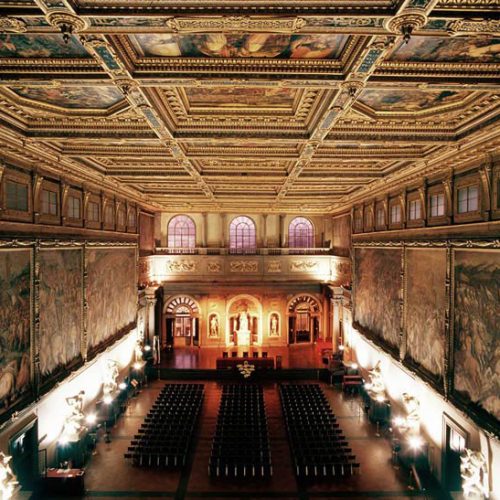

The choice of exhibiting Gazing Ball (Barberini Faun) in the Room of the Lilies, a lavish environment decorated with precious frescoes by Domenico Ghirlandaio (1449-1494) and a fake tapestry displaying the Angevin golden irises in a blue field, shows the intention of creating a dialogue between the Renaissance artistic language and the contemporary one. The room also hosts the original bronze sculpture by Donatello called Judith and Holofernes, one of the most fascinating and significant artworks of the fifteenth century. Facing Donatello’s masterpiece – Judith implacably punishing Holofernes, who was lured by the virginal beauty of the young woman, weakened by wine, then finally beheaded – the Barberini Faun of Koons’s sculpture will offer itself to the public with its revealing pose, an example of the beauty of the nude human body that is not vulgar, though pushed to a limit bordering the erotic. The obvious exhibition of nudity, showing the genitals, in a clearly sensual pose, that conveys a wild sexual power, will seem to provoke Judith herself, she who punishes the libidinous excesses, sensual inebriation, as recalled by the bacchanalia sculpted in bas relief on the base. The reflective blue sphere will, furthermore, interact with the bronze piece, and then with the decorative background of the room, with its dominant colors and the precious wooden ceiling. Such contrasts are exalted by Koons; highlighting the daily and the eternal, classical beauty and popular aesthetics, the mythical sphere and the earthly, childhood and history, Eros and Thanatos. At the same time, the interplay between balance and instability, original and copy, artwork and object, invites us to reconsider the relationship between imagination and mass production, between metaphysics and low materialism, between wonder and mystification, between classical idols and post-modern simulacra.

Other relations and meanings will stem from Piazza della Signoria where, not far from the marble copy of Michelangelo’s David, a sculpture from Koons’sAntiquity series will be displayed, that is, Pluto and Proserpina (2010-2013), a huge work reaching over three meters, made in mirror-polished stainless steel, with transparent color coating and live flowering plants. The two figures of Pluto and Proserpina, clinging to each other in a dramatic and sensual embrace, will shine in the daylight and, illuminated by night, are bound to create a jarring contrast with the pieces in marble and bronze in the square. The reflective surface of Koons’s work in front of Palazzo Vecchio will absorb, mirror, and liquefy all the surrounding space, with effects of blinding radiance. The shapes of the God of the underworld himself and those of his future spouse – the Greeks called her Persephone – will appear to melt into an almost gelatinous and strongly sensual matter, leading to a figurative dissolution, losing their iconographic features, their mythological premise and the Baroque morphology that Koons freely reinterprets in his works. Indeed, Pluto and Proserpina by Koons references a famous work by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, the Rape of Proserpina (225 cm, base 109 cm), made by the artist for the cardinal Scipione Caffarelli Borghese between 1621 and 1622, when Bernini was only 23 years old. In the documents of the time, the work is described as follows: “A Proserpina of marble and a Pluto carrying her away of about 12 palms of height, with a three-headed dog on the marble pedestal showing verses in the front.” As is well known, Maffeo Barberini, later to become Pope Urban VIII, was so impressed by it that he composed a couplet inspired by the group showing Pluto seizing Proserpina. In Dodici distichi per una Galleria, illustra, con epigrammi e brevi descrizioni, dodici quadri di una galleria immaginaria he writes: “ Oh, you who bend down to pick flowers from the earth, look at me who have been abducted to the home of cruel Pluto” This is why a privileged viewpoint to appreciate the work is from the front, where the inscription by Maffeo Barberini is found. Studying Bernini’s sculpture, we therefore realize that Pluto has already dropped his two-forked scepter to vigorously seize the young woman, who in turn tries to free herself with her right hand raised towards the sky, rendering with great virtuosity the meaning of the poem’s “look at me.”

The moment in which the God of the underworld assaults Ceres’ daughter, while she is collecting flowers in the woods by a lake, is described in theMetamorphosis by Ovid. The goddess “was having fun picking violets and snow white irises, collecting them with childish enthusiasm in baskets and with the hems of her dress, competing with her friends as to who picked more of them, when Pluto suddenly saw her, took a fancy and seized her: so impetuous was his passion. The goddess, terrified, cried out for her mother and friends, but more for her mother; and since the hem of her dress was torn, all the flowers fell to the ground: so pure the girl was, that the loss of the flowers, too, was painful to her virginal heart.” The myth, according to scholars, refers to the change of seasons: the cold and frost of winter, the rebirth of springtime. Pluto, indeed, in the literary tradition is also described as the image of the Sun. For example Cartari (c.1531–1569), the author of a fundamental text for Renaissance iconography, states: “Pluto, meaning the Sun, seized her and brought her along with him to hell, because the sun’s heat, throughout winter, nurtures and keeps the underground sown grain”. According to Varro, quoted by Saint Augustine, the name Proserpina could derive from proserpere, referring to the seed coming out of the soil. In the marble by Bernini, Proserpina, as beautiful as the Venus by Praxiteles, is fighting in vain for her pureness. She screams, opening her mouth wide, invoking her mother and friends. In her eyes one can read different emotions: shame for her abused nudity, fear for Pluto’s erotic frenzy, desperation because the girl is about to discover the darkness of the underworld. Ovid’s verses clarify the presence of fresh flowers added by Jeff Koons, with philological precision, to his stainless steel sculpture whereas unlike Bernini he omits the figure of the dog Cerberus. Pluto and Proserpina by Koons will be displayed in front of Palazzo Vecchio (from the 25th of September) right next to the copy of David, a universal symbol of the Florentine Renaissance as much as the Primavera by Botticelli at the Uffizi. There is a different and subtler relation between Koons’s work and the background offered by Piazza Signoria; the sense of art, beauty and love as an ongoing rebirth, as the sublimation of pain and the overcoming of death (even of art’s death). Indeed, in Pluto and Proserpina’s myth, the primordial power of Eros to spread death and violence – both spiritual and physical – is counterbalanced by beauty and love’s creating power, by the vital and radiant union of male and female, as that of history and imagination. The special collocation of Koons’s Pluto and Proserpina was also chosen to highlight its affinity with Giambologna’s Rape of the Sabines under the Loggia dei Lanzi and with Michelangelo’s Genie of Victory placed in the Salone dei Cinquecento in Palazzo Vecchio, two of the greatest examples of a spiraliform treatment of the movement of a body. Evidently, Bernini owed a lot to the art of the sixteenth century in the creation of his masterpiece Rape of Proserpina. Critics believe Bernini must have studied first the Hercules and Antaeus by Giambologna (1529-1608), then drew inspiration from a work by a certain Pietro da Barga (documented from 1574 to 1588), who made a statue of the same subject in bronze probably inspired by Pliny, who in his Naturalis Historia, (XXXIV, 69) mentioned a bronze group by Praxiteles representing the “Raptus Proserpinae.”

That is why the exhibition Jeff Koons In Florence results in a sophisticated and joyful game of quotations and cross-references, of contrasts and comparisons between the ancient and the contemporary, where the reflective surface hides the obscure and magical meaning of creation with an apotropaic function as well.

The exhibition opens on the 26th of September and runs until the 15th of Jenuary 2016.

The show arose from Fabrizio Moretti’s proposal and is curated by Sergio Risaliti.

Promoted by the Comune di Firenze, it is organized by Mus.e with the contribution of Camera di Commercio, Moretti Fine Art and David Zwirner with the collaboration of Biennale Internazionale di Antiquariato di Firenze.