Dante Alighieri, gli Uomini illustri e il Bene comune

al 16 Gennaio 22

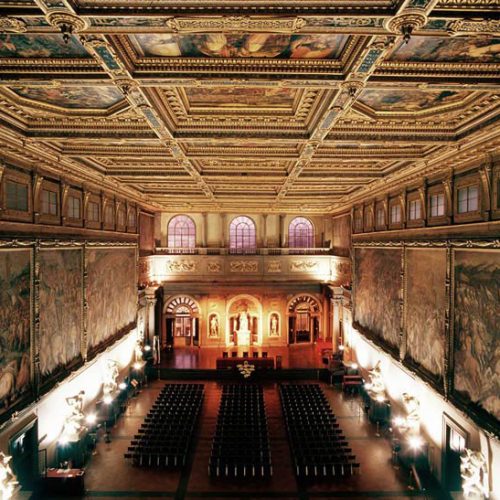

Negli anni Ottanta del Trecento Dante, ormai riabilitato in città e già largamente celebrato per la sua opera, viene individuato fra gli esempi di virtù da raffigurare entro un ciclo dipinto all’interno di Palazzo Vecchio: ventidue uomini illustri della storia, emblemi di alti valori etici e politici, in grado di ispirare i governanti cittadini.

La serie fiorentina – concepita da Coluccio Salutati, notaio, intellettuale e cancelliere della Repubblica fiorentina -, oggi perduta, si inseriva nel solco della pittura civica e politica sviluppatasi nel corso del Trecento fra i Comuni italiani, tesa a rappresentarne in forma diretta ed efficace il messaggio politico. Entro tale contesto si collocava infatti l’idea di Bene comune, inteso come bene di una comunità, da difendere rispetto agli interessi personali e di fazione; a corollario di questa superiore entità politica ed etica, infatti, assumevano un posto di rilievo le virtù, suoi fondamentali presidi, ma anche le figure esemplari della storia che le avevano ben incarnate.

Gli Uomini illustri del palazzo fiorentino erano nove eroi della repubblica romana, due condottieri, sei grandi monarchi e cinque poeti toscani, nel seguente ordine: Bruto, Furio Camillo, Scipione l’Africano, Curio Dentato, Dante Alighieri, Pirro, Annibale, Francesco Petrarca, Fabio Massimo, Marco Marcello, Nino, Alessandro Magno, Claudiano, Zanobi da Strada, Giovanni Boccaccio, Giulio Cesare, Ottaviano Augusto, Costantino, Carlo Magno, Cicerone, Fabrizio Luscinio e Catone Uticense.

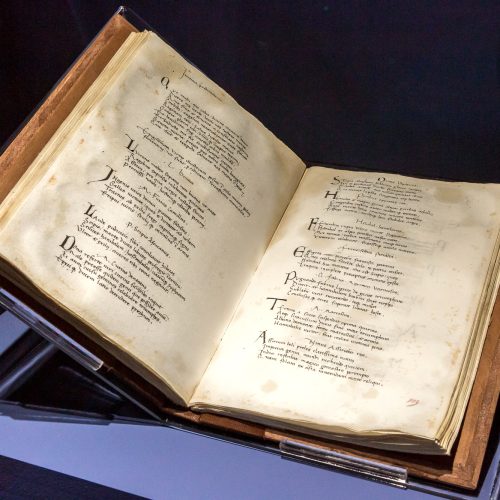

Il messaggio civico, etico e politico era esplicitato con ancor maggior chiarezza dalle iscrizioni poste a corredo degli effigi, in un concorso perfetto fra poesia e pittura: ogni personaggio era infatti accompagnato da un titulus, che esplicitava le caratteristiche distintive per cui la singola figura era stata scelta per comparire nel ciclo. Abbiamo la testimonianza diretta delle iscrizioni presenti grazie a un manoscritto della Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana (Conventi Soppressi 79), straordinariamente esposto in sala (in replica, dopo il 25 ottobre in originale) e aperto proprio sulle pagine dedicate agli Uomini illustri.

Negli anni Settanta del Quattrocento vengono avviati importanti lavori su questo ambiente e su quello adiacente, con il rinnovo dell’intero programma decorativo: echi della serie originaria si hanno tuttavia nei sei eroi romani affrescati da Domenico Ghirlandaio e nei due battenti lignei della porta monumentale di accesso alla sala, che ripropongono in intarsio proprio Dante e Petrarca.

Gli Uomini illustri fiorentini, in cui l’Alighieri aveva un posto d’onore, viene oggi qui reinterpretato in chiave contemporanea e riproposto al pubblico come elemento ispiratore del nostro agire individuale e collettivo: oltre all’esposizione del codice laurenziano con le iscrizioni correlate ai personaggi, infatti, chiunque entrerà nella Sala dei Gigli fra la metà di ottobre e la metà di novembre potrà fruire di un’installazione sonora immersiva inedita, frutto del lavoro accurato e creativo del team di sound designer di Mezzo Forte. Il progetto sonoro dispiegato nell’ambiente – rispettoso della sala e nello stesso tempo aderente alla stessa – è stato infatti sviluppato connotando ogni singolo personaggio e inserendolo in una più ampia sequenza, che intreccia da una parte l’età medievale e dall’altra il tempo contemporaneo.

Per un mese il pubblico potrà così visitare la sala immergendosi in una ricca e avvincente stratigrafia storica, che dal Trecento giunge fino a noi armonizzando in forma assolutamente unica linguaggi artistici differenti e fra loro distintivi: gli affreschi dipinti, gli intarsi lignei, gli esametri latini, la composizione sonora concorreranno infatti nel disegnare un tessuto narrativo composito e articolato, che dal passato trae nutrimento per un’indagine tutta attuale sull’idea di bene comune. Quale espansione fisica e temporale del progetto, tutti i contenuti sonori e testuali saranno inoltre fruibili su una pagina dedicata del sito MUS.E, unitamente alla visione panosferica della sala dei Gigli: un’ulteriore e potente cassa di risonanza dell’iniziativa, che risuonerà virtualmente dal 15 ottobre fino al 31 dicembre 2021.

In aggiunta, nelle giornate di venerdì, sabato e domenica (dalle 10 alle 13 e dalle 14 alle 18) il progetto conoscerà un’ulteriore interpretazione, questa volta teatrale: la giovane compagnia I Nuovi, “costola” del Teatro della Pergola, concorrerà infatti alla restituzione del ciclo medievale e di ciò che esso costituiva agli occhi della città grazie a una performance ideata appositamente per l’occasione: i personaggi sembreranno così tornare in vita, offrendosi allo sguardo del pubblico per sottolineare, ancora una volta, quanto i valori e le virtù impersonate dalle diverse figure della storia siano ancora oggi riferimenti importanti per il nostro pensare e il nostro agire collettivo.

Scarica la brochure del progetto>>

Scarica il booklet del progetto>>

Ascolta i file audio dell’installazione in Sala dei Gigli>>

Lucio Giunio Bruto

Io, vendicatore di Lucrezia, “Il saggio” e non più “Lo sciocco” come prima, dopo aver espulso i re da Roma, ho donato ai Quiriti la libertà, per la quale ho abbattuto i figli [del re] a suon di bastonate e con la scure infallibile, e morendo ho ucciso il mio nemico.

Marco Furio Camillo

Io, Camillo, con la mia destrezza piegai Veio, con il mio rigore morale i Falischi, con il mio coraggio i Galli. Li annientai, e tornai a Roma da dittatore. Sottrassi ai vinti le insegne militari che avevano conquistato, e invecchiai tra le armi.

Publio Scipione Africano

Con i meriti dovuti alla sua clemenza Scipione si conquistò il favore degli abitanti dell’Iberia, annientò in guerra i comandanti libici, Annibale, i due Asdrubale e lo sleale Siface, e, vendicandosi dell’esilio [a cui si era ritirato], a te, Roma, negò [la sepoltura] del suo corpo.

Manio Curio Dentato

“O ambasciatori, riportate indietro i vostri doni!”– disse Curio ai Sanniti – “Preferisco dominare su un popolo che possiede dell’oro [piuttosto che avere dell’oro io stesso], celebrare un doppio trionfo nel corso di un anno e allontanare dal Lazio [la minaccia di] Pirro, re dell’Epiro”.

Dante Alighieri

Dante, gloria eccelsa della famiglia Alighieri, Firenze ti rappresenta qui, insieme a così grandi condottieri, affinché tutti conoscano l’autore che cantò delle anime cadute [per sempre], di quelle destinate a salire [in cielo] e di quelle beate.

Pirro, re dell’Epiro

Io, Pirro, della stirpe antica di Ercole e del grande Achille, campione nel cingere in assedio gli accampamenti [nemici] e vendicatore di Taranto, dopo aver tentato di vincere i Romani con l’oro, con la guerra e con l’inganno, sconfitto fuggii, e caddi – oh, disgraziato me! – ad Argo.

Annibale, figlio di Amilcare

Io, Annibale, dopo aver rotto l’alleanza [con i Romani], distrussi in guerra Sagunto e, astutamente, mi aprii una strada nelle Alpi [frantumando] con l’aceto [i massi che ostacolavano il cammino]. Mi celebrano come vincitore a Canne, sulla Trebbia, al Trasimeno e al Ticino, e per aver fuggito le catene [della schiavitù] con il veleno.

Francesco Petrarca

Francesco Petrarca, la patria pone [anche] te tra le immagini dei grandi, che tu celebri con il tuo stile ornato. Qui c’è Annibale morente, lì Scipione, dei quali tu, rapito [dalla morte prima del tempo], abbandoni le gesta lasciando il tuo canto incompiuto.

Quinto Fabio Massimo, il Verrucoso

Combattendo Fabio riportò il trionfo sul popolo ligure. Ma temporeggiando vinse due volte Annibale, imbaldanzito dalla fortuna di una doppia vittoria, e, sconfitto il nemico, libera te, o Minucio, e le schiere ormai accerchiate.

Marco Marcello

Il feroce Marcello consacrò per terzo al sacro Quirino le spoglie opime [del nemico sconfitto] e celebrò il trionfo su Siracusa, contro l’uso, sul Monte Albano. Vincitore di Annibale in guerra, fu vittima illustre del Cartaginese.

Nino, re degli Assiri

Io, Nino, figlio illustrissimo del re Belo, diedi vita all’impero assiro, turbando la quiete del mondo. Dopo aver ucciso il mago Zoroastro, rimaneva [ancora] l’India, che sola di tutta l’Asia con la mia morte lasciai da conquistare.

Alessandro Magno, re dei Macedoni

L’insigne Alessandro, dopo aver vendicato la morte del padre, distrusse la ribelle Tebe e risparmiò la dotta Atene. Sottomise i Persiani, gli Sciti, gli abitanti della Battriana e dell’India, lui che, richiesti con insistenza onori divini, morì di febbre a Babilonia.

Claudiano, poeta fiorentino

Nato in Egitto, mi riconobbe come suo cittadino Firenze, inesperta nelle leggi, ma già degna di grandi poeti. Cantai il ratto [di Proserpina] nell’Ade e le battaglie degli dei [nella Gigantomachia], lodi in onore dell’imperatore e omaggi a Stilicone.

Zanobi da Strada

A causa della dedizione alle Muse, Zanobi meritò di essere ascritto tra i grandi poeti e di avere le tempie cinte della corona di alloro. E mentre moltissime opere ne mostrano l’ingegno, l’offesa di una morte prematura – ahimè, [che] dolore! – se ne portò via il frutto.

Dominus Giovanni Boccaccio

O illustre Giovanni, famosa progenie della famiglia Boccaccio, tu che celebri tutta la discendenza degli dèi, la vita agreste e le vicende illustri degli uomini, e dai ogni onore alle donne, Firenze ti ha ritratto qui per i tuoi meriti.

Caio Giulio Cesare

Cesare, feroce in guerra, mitissimo dopo aver deposto le armi, rifulge vittorioso dopo aver celebrato sul nemico cinque trionfi. Le guerre galliche, quelle presso Faro [in Egitto], sul Mar Nero, in Libia e presso il fiume Ebro sono gloria per il vincitore. La Curia [di Roma] è testimone della sua morte.

Ottaviano Augusto

Azia mi generò. Il dittatore Cesare mi adottò. Annientai Bruto con gli altri cesaricidi e i loro alleati, sacrifici in onore di mio padre. Celebrai il trionfo per tre volte, chiusi le porte del tempio di Giano, assunsi lo scettro dell’impero e il timone del mondo.

Costantino Imperatore

[San Pietro], portatore delle chiavi del cielo, facendomi immergere nell’acqua sacra [del Battesimo], libera me, Costantino, dalla lebbra e insieme dal peccato, motivo per cui ho meritato di essere lo scopritore [dei frammenti] della sacra croce. E decisi di onorare Bisanzio del trono imperiale.

Carlo Magno

Io, Carlo, soprannominato Magno, re dei Galli, domai il popolo e i re dei Longobardi e, conquistatomi l’impero, ti fornii di forti mura, Firenze mia, accresciuta [com’eri] di [nuovi] cittadini romani.

Marco Tullio Cicerone

Tullio [Cicerone] fu insigne autore dell’eloquenza in lingua latina. Roma stimò il suo ingegno pari ai propri trionfi e alla propria potenza. Represse [la congiura di] Catilina, ma la spada di Antonio uccise lui e la libertà.

Gaio Fabrizio Luscino

Chiamato da Pirro, che gli voleva donare la quarta parte del suo regno perché povero, Fabrizio disprezzò le offerte del re e i doni dei Sanniti, e per questo si disse che quel campione di onestà era più irremovibile di quanto lo fosse il sole nel percorrere il proprio corso [nel cielo].

Marco Porzio Catone l’Uticense

Onore delle virtù, concepito nel grembo dell’onestà, io sono quel Catone che, sempre acerrimo nemico dei vizi, si pronunciò per la pena di morte dei congiurati. Esalando l’ultimo respiro, tornai libero alle mie stelle.

Promossa dal Comune di Firenze, nell’ambito delle celebrazioni per il centenario della morte di Dante Alighieri e in omaggio alla memoria e agli studi di Maria Monica Donato e Giuliano Tanturli

A cura di Valentina Zucchi e Carlo Francini

Organizzazione MUS.E

Con il supporto di, Aquila Energie e Libera Accademia di Belle Arti Firenze

Progetto allestitivo, Tratto di Luigi Cupellini

Allestimento Acme 04

Ente Prestatore, Ministero della Cultura – Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana

Installazione sonora 3D, Mezzo Forte

Perfomance teatrale, Associazione I Nuovi

Panosferica Sala dei Gigli, Artnine PhotoStudio

Original musics are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

and are available at the following url https://soundcloud.com/user-329420512-318437541/sets/uomini-illustri-palazzo-vecchio